Baseball's Funeral

When I asked, Greg hadn’t seen it. Will hadn’t seen it. Brett hadn’t seen it. Jordan hadn’t seen it. Neither Mike nor Gion had seen it. Hutch hadn’t seen it. Phil hadn’t seen it. Warren hadn’t seen it.

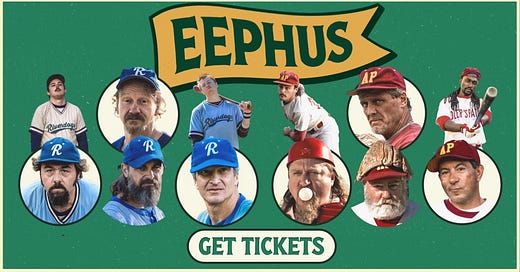

I’m talking about the new baseball movie Eephus, the directorial debut of Carson Lund, which opened around the country at the start of spring and garnered fond coverage in the NY Times, The New Yorker, and on NPR. The AP’s Jake Coyle called it, “The best baseball film since Moneyball”--praise that manages to be bombastic and faint at once.

Since it’s unlikely you’ve seen it, let me tell you what happens near the end: The sun sets and the game between rec league teams Adler’s Paint and the Riverdogs is tied. It’s mid-October in central Massachusetts. The men’s breath becomes visible in the dusk. They don’t want to keep playing, but they refuse to stop. This is their last game on a field that’s about to be demolished.

At one point, a ball is hit high into the dark sky and no one sees or hears it land. The Riverdogs’ third-base coach, a combat veteran, wanders the nearby woods looking for it. When no one can see at all, player-manager Graham Morris, whose construction company will eventually raze the field, insists, impossibly, that “There are ways to play without light.” The other players, who have called him things like “bulldozer boy” all game, ridicule him for this idiocy, too. Soon after, however, men from both teams position their cars around the field and partially illuminate it with their headlights. They persist in this beleaguered way for a few more innings before the game ends on a walk-off walk.

When I saw Eephus in the Edina Mann Theater on a snowy Wednesday in early April, the movie’s denouement made me sure I was watching a funeral for baseball. I didn’t want to see a funeral for baseball, so I can’t say that I enjoyed the experience. I didn’t like how the players lollygag through a world that has no room for them. I didn’t like that Lund cast them almost as old baseball cards come to life, with each wearing a bit too readily his sense of himself as a real piece of work. I didn’t like how the camera fetishizes their bouncing beer bellies as they take the field. I did like when Bill “Spaceman” Lee wanders in from the woods, assures the Adler’s Paint guys that he can get them three outs, then takes the mound and does. I did like the film’s reverence for the New England afternoon. But, I didn’t like the overly affected relief pitcher who described the high-arcing pitch that gives the movie its name as “something you get bored watching.”

I got bored watching. More than bored, I became restless. However big the demographic of literary-minded, nostalgia-pilled, middle-aged baseball fans happens to be, I’d place myself near the bullseye of that group. I felt caught almost in the headlights used to light the field.

It’s disconcerting when media seems aimed too squarely at you. I don’t appreciate it when Jason Isbell seems to be singing about my actual relatives, or when Judd Apatow tells me how to be 40. I like to think of baseball as a spiritually inflected agrarian pastime that celebrates the warm months between the equinoxes. To me, baseball is one of the few things that is redeemable about being American, a tradition that stands against increasingly dire expressions of capitalism.

This is why I couldn’t warm to Lund’s suggestion that baseball is over. I didn’t dislike Eephus because he’s wrong. I disliked it because he’s right. The movie takes place sometime in the early 1990s. Baseball movies of that era--Bull Durham, Field of Dreams, Major League-- celebrate a vibrant and quirky pastime. All Eephus can do is mourn. It seems almost too clever that the movie is set just before or just after the signing of NAFTA. This choice allows Eephus to portray a leisure activity easily undone by the offshoring of American manufacturing, while the men’s brittleness prefigures the rise of Trump and our current epidemic of loneliness.

In the days after I saw Eephus, the snow melted, the movie’s syrupy cinematography lingered in my mind, and I wondered if I was being too cynical. The movie became available for streaming and my friend Greg finally watched it. He told me he laughed at the parts I complained about and said in general he enjoyed it.

So, I rented it and put it on in the background while I completed some mindless work. It was Easter Monday. Having been made to confront baseball’s death, I could believe Eephus also represented its resurrection. It’s a game no longer central to American life, but it’s still there, persisting in professional ballparks and on tv, if not as regularly in adult rec leagues. I thought how amazing that the game exists at all. I hoped there might still be ways to play even without light.